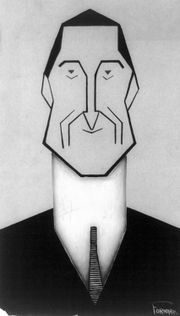

William Gibbs McAdoo

| William Gibbs McAdoo | |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office March 6, 1913 – December 15, 1918 |

|

| Preceded by | Franklin MacVeagh |

| Succeeded by | Carter Glass |

|

|

|

| In office March 4, 1933 – November 8, 1938 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel M. Shortridge |

| Succeeded by | Thomas M. Storke |

|

|

|

| Born | October 31, 1863 near Marietta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | February 1, 1941 (aged 77) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Hazelhurst Fleming (1885-1912 [her death]) Eleanor Randolph Wilson (1914-1934 [divorce]) Doris Isabel Cross (1935-1941 [his death]) |

| Alma mater | University of Tennessee |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

William Gibbs McAdoo, Jr.[1] (October 31, 1863 – February 1, 1941) was an American lawyer and political leader who served as a U.S. Senator, United States Secretary of the Treasury and director of the United States Railroad Administration (USRA). By virtue of his position as Secretary of the Treasury, in August 1914, he served as an "ex-officio member" on the first Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC.

Contents |

Early life and career

McAdoo was born near Marietta, Georgia, to author Mary Faith Floyd (1832-1913) and attorney William Gibbs McAdoo (1820-1894). His uncle, John D. McAdoo, was a Civil War general and justice on the Texas Supreme Court.[2] McAdoo attended rural schools until his family moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1877, when his father became a professor at the University of Tennessee.

He graduated from the University of Tennessee and is an initiate of the Kappa Sigma Fraternity Lambda Chapter at the University of Tennessee. He was appointed deputy clerk of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee in 1882. He married his first wife, Sarah Hazelhurst Fleming, on November 18, 1885. They had seven children: Harriet Floyd McAdoo, Francis Huger McAdoo, Julia Hazelhurst McAdoo, Nona Hazelhurst McAdoo, William Gibbs MacAdoo III,[1] Robert Hazelhurst McAdoo, and Sarah Fleming McAdoo.

He was admitted to the bar in Tennessee in 1885 and set up a practice in Chattanooga, Tennessee. In 1889, he lost most of his money trying to electrify the Knoxville Street Railroad system.[3] In 1892 he moved to New York City, where he met Francis R. Pemberton, son of the Confederate General John Pemberton. They formed a firm, Pemberton and McAdoo, to sell investment securities.

At the turn of the century, McAdoo took on the leadership of a project to build a railway tunnel under the Hudson River to connect Manhattan with New Jersey. A tunnel had been partly constructed during the 1880s by Dewitt Clinton Haskin. With McAdoo as President of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company, two passenger tubes were completed and opened in 1908. The popular McAdoo told the press that his motto was "Let the Public be Pleased." The tunnels are now operated as part of the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) system.

His first wife died in February 1912. That year, he served as vice chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

In March 1919, McAdoo co-founded the law firm McAdoo, Cotton & Franklin, now known as white shoe firm Cahill Gordon & Reindel. He left the firm in 1922 and moved to California to continue his political career.

Political career

Woodrow Wilson lured McAdoo away from business after their meeting in 1910. He worked for the Wilson presidential campaign in 1912. Once he was President, Wilson appointed McAdoo Secretary of the Treasury, a post McAdoo held from 1913 to 1918.[4][5][6]

He married Wilson's daughter Eleanor Randolph Wilson at the White House on May 7, 1914.[7] They had two daughters, Ellen Wilson McAdoo (1915-1946) and Mary Faith McAdoo (1920-1988). Ellen married twice and had two chldren.[8] Her parents adopted her elder son after her death, and he took their surname.

McAdoo offered to resign when he married the President’s daughter but Wilson urged him to complete his work of turning the Federal Reserve System into an operational central bank. The legislation establishing the System had been passed by Congress in December 1913.

As head of the Department of the Treasury McAdoo confronted a major financial crisis on the eve and at the outbreak of World War I, July - August 1914.[9] During the last week of July, 1914, British and French investors began to liquidate their American securities holdings into U.S. currency. Many of these foreign investors then converted their dollars into gold, as was common practice in international monetary transactions at the time, in order to repatriate their holdings back to Europe. If they had done this, they would have depleted the gold backing for the dollar, possibly inducing a depression in American financial markets and in the American economy as a whole. They might then have been able to buy American goods and raw materials (for their war effort) at greatly depressed prices, which the Americans would have had to accept in order to re-start the economy from a consciously (albeit inadvertently) caused depression.

McAdoo's actions at the time were both bold and outrageous. The United States in 1914 was still a net debtor nation (i.e., Americans' aggregate debt to foreigners was greater than foreigners' aggregate debt to Americans). The nations of Europe and their financial institutions held far more in debt of the United States; of many of the states of the Union; and of American private institutions of all kinds, than investors in the United States held in the debt of Europe's nations and institutions in all forms, both public and private.

McAdoo kept the U.S. currency on the Gold Standard. He arranged the closing of the New York Stock Exchange for an unprecedented four months in 1914 to prevent Europeans from selling American securities and exchanging the proceeds for dollars, and then gold.

Economist William L. Silber wrote that the wisdom and historical impact of this action cannot be overemphasized[9]. McAdoo’s bold stroke, Silber writes, as a first consequence averted an immediate panic and collapse of the American financial and stock markets. But also, it laid the groundwork for an historic and decisive shift in the global balance of economic power, from Europe to the United States; a shift which occurred exactly at that time. More than this, McAdoo's actions both saved the American economy and its future allies from economic defeat in the early stages of the war.

Investors in the warring countries had no access to their holdings of US financial assets at the outset of the war because of McAdoo’s actions. As a result, the treasuries of those countries more-quickly exhausted all of their net foreign exchange holdings (those that were on-hand and in their possession before McAdoo closed the markets), currency, and gold reserves. Some of them then issued sovereign bonded indebtedness (IOUs) to pay for the war materials they were buying on the American and other markets.

Silber wrote that the intact and undamaged American financial system and its markets managed the flow and operation of this financing more easily than they would have without McAdoo's measures, and that US industry swiftly built up to the scale needed to meet the allied war needs. The managed liquidation of foreign holdings of US assets moved the United States to a net creditor position internationally and with Europe from the net debtor position it had held prior to 1915.

In order to prevent a replay of the bank suspensions that plagued America during the Panic of 1907, McAdoo invoked the emergency-currency provisions of the 1908 Aldrich Vreeland Act. William Silber credits his actions for having turned America into a world financial power, in his book When Washington Shut Down Wall Street.[9]

After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the United States Railroad Administration was formed to run America’s transportation system during the war. McAdoo was appointed Director General of Railroads, a position he held until November 1918 when the armistice was declared, ending World War I.

After leaving the Wilson Cabinet, he focused on his law firm, which included serving as general counsel for the founders of United Artists.[10] He ran twice for the Democratic nomination for President, losing to James M. Cox in 1920,[11] and to John W. Davis in 1924,[12] even though in both years he led on the first ballot.[13][14][15] The 1924 nomination was notable due to the Ku Klux Klan endorsement of McAdoo; he did not condemn the nomination. He served as Senator for California from 1933–1938. He was defeated for renomination to the Senate in 1938 by Sheridan H. Downey. McAdoo and Eleanor were divorced in 1934.[16] Two months after the decree was finalized in July 1935, the 71-year old married 26-year-old nurse Doris Isabel Cross.[17][18]

McAdoo was a "Dry" with respect to Prohibition. McAdoo took a payment of $25,000 from oil executive Edward Doheny in connection with the Teapot Dome scandal, but returned it once he discovered Doheny's links with Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall.

Death and legacy

McAdoo died of a heart attack while traveling in Washington, D.C., after the third inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt,[19] and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.[20]

McAdoo was played by Vincent Price in the 1944 biopic Wilson. McAdoo's former home in Chattanooga's Fort Wood neighborhood has been restored and is now a private residence.

The town of McAdoo in Dickens County, Texas, is named for him.[21] McAdoo's Seafood Company, a restaurant in New Braunfels, Texas, also bears his name.

McAdoo is quoted as having said, "It is impossible to defeat an ignorant man in argument."

Bibliography

- Broesamle, John J. William Gibbs McAdoo: A Passion for Change, 1863-1917. National University Publications, Kennikat Press, Port Washington, N.Y., 1973, ISBN 978-0-8046-9043-0

- McAdoo, William G. The Challenge. New York: Century Co., 1928.

- McAdoo, William G. Crowded Years: The Reminiscences of William G. McAdoo. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1931, ASIN B000OALAE6

- McKinney, Gordon B. "East Tennessee Politics: An Incident in the Life of William Gibbs McAdoo, Jr." East Tennessee Historical Society’s Publications 48 (1976): 34-39.

- Synon, Mary. McAdoo, the Man and His Times: A Panorama in Democracy. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1924.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

- Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820-1894) - sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

- William Gibbs McAdoo (1863-1941) - sometimes called "II" or "Junior"

- Lt. William Gibbs McAdoo, Jr. (1895-1960) - sometimes called "III"

- ↑ TSHA Online - Texas State Historical Association - Home at www.tshaonline.org

- ↑ Imjort, et al. (August 22, 1938). California's McAdoo . Time

- ↑ Shook, Dale N. William G. McAdoo and the Development of National Economic Policy, 1913-1918. NY: Garland Publishing, 1987.

- ↑ Staff report (February 26, 1913). FOUR MEN CERTAIN IN WILSON CABINET; Bryan, McAdoo, Burleson, and Daniels Accept -- Walker for Attorney General. New York Times

- ↑ Staff report (March 6, 1913). CABINET MEMBERS SWORN.; McReynolds, Houston, and McAdoo Take Oath of Office . New York Times

- ↑ Staff report (May 8, 1914). ELEANOR WILSON WEDS W.G. M'ADOO; President's Youngest Daughter and Secretary of Treasury Married at White House. New York Times

- ↑ Staff report (December 23, 1946). M'ADOO'S DAUGHTER FOUND IN COMA, DIES. New York Times

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Silber, William L., When Washington Shut Down Wall Street: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914 and the Origins of America's Monetary Supremacy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 2007, ISBN 978-0-691-12747-7

- ↑ Pietruza, David. 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents. Carroll & Graf Publishers, ISBN 0-7867-1622-3

- ↑ Bagby, Wesley M. “William Gibbs McAdoo and the 1920 Democratic Presidential Nomination.” East Tennessee Historical Society’s Publications 31 (1959): 43-58.

- ↑ Allen, Lee N. “The McAdoo Campaign for the Presidential Nomination in 1924.” Journal of Southern History 29 (May 1963): 211-28.

- ↑ Gelbart, Herbert A. “The Anti-McAdoo Movement of 1924.” Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 1978.

- ↑ Stratton, David H. “Splattered with Oil: William G. McAdoo and the 1924 Democratic Presidential Nomination.” Southwestern Social Science Quarterly 44 (June 1963): 62-75.

- ↑ Prude, James C. “William Gibbs McAdoo and the Democratic National Convention of 1924.” Journal of Southern History 38 (November 1972): 621-28.

- ↑ Staff report (July 18, 1934). Eleanor Wilson McAdoo Divorces Senator At Five-Minute Hearing on Incompatibility.New York Times

- ↑ Staff report (September 15, 1935). M'ADOO WEDS NURSE IN COLONIAL STYLE; Senator, 71, and Bride, 26, Take Vows in Flower-Decked Home of Son-in-Law.New York Times

- ↑ Staff report (September 23, 1935). No. 3 for McAdoo. Time

- ↑ Staff report (February 2, 1941). William G. M'Adoo Dies in the Capital of a Heart Attack; Former Senator, Secretary of Treasury Under Wilson, Was Railways Director in War. Builder of Hudson Tubes. He Swung 1932 Nomination to Roosevelt -- Backed for the Presidency in '20 and '24. New York Times

- ↑ Staff report (February 10, 1941). Footnote to History. Times

- ↑ TSHA Online - Texas State Historical Association - Home at www.tshaonline.org

External links

- William Gibbs McAdoo at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- William Gibbs McAdoo via arlingtoncemetery.net

- Who's Who: William Gibbs McAdoo

- William Gibbs McAdoo via Tennessee Historical Society

- Speeches by William Gibbs McAdoo via Library of Congress

- Anthony Fitzherbert (June 1964). "William G. McAdoo and the Hudson Tubes". Electric Railroaders Association, nycsubway.org. http://world.nycsubway.org/us/path/hmhistory.html. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Franklin MacVeagh |

United States Secretary of the Treasury Served under: Woodrow Wilson March 6, 1913 – December 15, 1918 |

Succeeded by Carter Glass |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Samuel M. Shortridge |

United States Senators from California March 4, 1933 – November 8, 1938 |

Succeeded by Thomas M. Storke |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Anthony Fokker |

Cover of Time Magazine 7 January 1924 |

Succeeded by Bishop William Lawrence |

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||